I. An Overview of Indonesian Military business

II. Businesses Owned by Military

Companies owned in whole or in part by the Indonesian military span the full range of the economy, from agribusiness to manufacturing and from golf courses to banks. In September 2005 the TNI complied with a request from the Ministry of Defense for an inventory of its business interests.[1] (Preparation of the inventory was a first step toward implementing the TNI law passed a year earlier that mandated the transfer of these businesses to government control.) The initial inventory identified 219 military entities (foundations, cooperatives, and foundation companies) engaged in business activity.[2]

As of March 2006, the TNI had provided information on 1,520 individual TNI business units.[3]

(See Data 1, below.) By April 2006, the Ministry of Defense had initiated a separate review process to examine whether its three foundations were engaged in business activity.[4]

Source: Ministry of Defense letter to Human Rights Watch, December 22, 2005; Maj. Gen. Suganda, then TNI spokesman, “TNI commits to reform[,] upholds supremacy of law,” opinion-editorial, Jakarta Post, March 15, 2006.

The TNI and other authorities who have access to the inventory results have not publicly identified the individual business interests held by the military or provided information on their total value. Officials involved in the review of the military’s businesses declined to share a copy of the inventory with Human Rights Watch, to provide the names of the businesses listed on it, or to reveal the businesses’ total declared value.[5 ]

They said the data supplied by the TNI could not be considered final because it was “very rough” and included many entities that, in their view, did not constitute “real businesses.”[6]

According to these officials, the list incorporated many small-scale ventures, some with assets of negligible value, alongside other, much larger enterprises.[7]

In the meantime, public statements offer some indications. In mid-2005, unnamed officials told the Singapore-based Straits Times newspaper that the top twenty or so military companies in Indonesia had a total estimated annual income of $200 million.[8]

For the sake of comparison, perhaps the best available historical figure is one used by foreign finance officials. An “informal review” of a selection of eighty-eight military businesses in Indonesia found that they had a combined turnover of Rp. 2.9 trillion ($348 million) in 1998/1999.[9] The Far Eastern Economic Review, referring to the same study, further revealed that annual revenue from the selected military businesses amounted to approximately Rp. 500 billion ($60 million).[10] Contrasting this to the $200 million figure offered in mid-2005 (which covered a smaller number of companies), it appears that those military businesses that survived the Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s were able to rebound significantly from that low point. (See below for additional data specifically for businesses held under military foundations.)

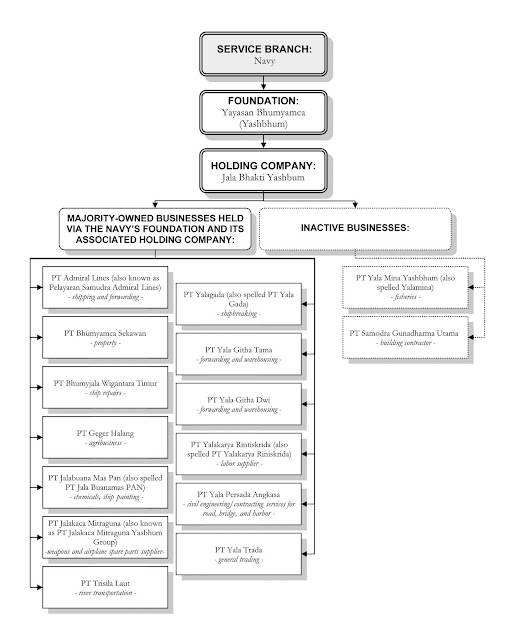

Note: This example is provided here to demonstrate the ownership structure of military businesses and does not purport to make a substantive claim about the businesses listed. It is based on information provided by TNI headquarters and supplemented by two people familiar with the navy’s businesses because they reviewed them (in one case, as part of an internal review by the navy and in the other independently). (Information as of May 2006.)

Link:

Bila ABRI berbisnis: menyingkap data dan kasus penyimpangan dalam praktik bisnis kalangan militer

Bisnis militer Orde Baru: Keterlibatan ABRI dalam bidang ekonomi dan pengaruhnya dalam rezim otoriter

Australian Defence Business Review

The Indonesian Military After the New Order

Power Politics and the Indonesian Military

Table of Contents

[1] In the Indonesian language, the defense ministry is called the Department of Defense but it is in English as

usually referred to as the Ministry of Defense.

[2] By comparison, according to a 2001 estimate provided by Minister of Defense Juwono Sudarsono, who

served a first term as defense minister from 1999 to 2000, the military then owned some 250 companies. ICG, “Indonesia: Next Steps in Military Reform,” ICG Asia Report, no. 24, October 11, 2001, p. 13. It is reasonable to assume that the 2001 figure reflected the outcome of an effort Sudarsono announced a year earlier, in which the defense ministry was “cooperating with the TNI headquarters to find out the number of foundations, cooperative units or companies owned by the TNI.” “Indonesian minister warns…,” AFP.

[3] Major General Suganda, “TNI commits to reform…,” Jakarta Post.

[4] Human Rights Watch interview with a person involved in that review, Jakarta, April 18, 2006.

[5] Human Rights Watch interview with Lt. Gen. Sjafrie Sjamsoeddin, secretary-general of the Ministry of Defense and former TNI spokesman, Jakarta, April 12, 2006; Human Rights Watch interview with Muhammad Said Didu (commonly known as Said Didu, the name used hereafter in this report), secretary of the Ministry of State-Owned Enterprises, Jakarta, April 19, 2006.

[6] The question of how the government would define military business for the purpose of implementing the TNI law’s mandate that these businesses be transferred to government control is discussed further below (see the chapter on “Obstacles to Reform”). Human Rights Watch interviews with Lt. Gen. Sjafrie Sjamsoeddin and Said Didu, April 2006.

[7] Ibid.

[8] John McBeth, “Tough job to wind up Armed Forces Inc,” Straits Times, June 4, 2005. The remaining formallyestablished military businesses were considered not to be economically viable. Ibid. Elsewhere, the total value of the military’s business holdings has been estimated, variously, at Rp. 326 billion (more than $35 million), Rp. 10 trillion ($1.06 billion), and more than $8 billion, to offer but a few examples. In most cases, it was unclear how these figures were calculated.

[9] The data was cited in a report prepared for international donors. World Bank, Accelerating Recovery in

Uncertain Times: Brief for the Consultative Group on Indonesia (Washington, DC: World Bank, 2000), p. 29.

[10] John McBeth, “The Army’s Dirty Business,” FEER, November 7, 2002. The article, presumably using 2002 exchange rates, gave the dollar equivalent as $55.5 million.

Book review:

READ MORE - Indonesian Military Business

II. Businesses Owned by Military

Companies owned in whole or in part by the Indonesian military span the full range of the economy, from agribusiness to manufacturing and from golf courses to banks. In September 2005 the TNI complied with a request from the Ministry of Defense for an inventory of its business interests.[1] (Preparation of the inventory was a first step toward implementing the TNI law passed a year earlier that mandated the transfer of these businesses to government control.) The initial inventory identified 219 military entities (foundations, cooperatives, and foundation companies) engaged in business activity.[2]

As of March 2006, the TNI had provided information on 1,520 individual TNI business units.[3]

(See Data 1, below.) By April 2006, the Ministry of Defense had initiated a separate review process to examine whether its three foundations were engaged in business activity.[4]

Data 1: Inventory of Military Businesses

Initial Inventory (September 2005)

Foundations 25

Companies under Foundations 89

Cooperative Units Engaged in Business 105

Revised Inventory (March 2006)

Total Individual Business Units 1520

Source: Ministry of Defense letter to Human Rights Watch, December 22, 2005; Maj. Gen. Suganda, then TNI spokesman, “TNI commits to reform[,] upholds supremacy of law,” opinion-editorial, Jakarta Post, March 15, 2006.

The TNI and other authorities who have access to the inventory results have not publicly identified the individual business interests held by the military or provided information on their total value. Officials involved in the review of the military’s businesses declined to share a copy of the inventory with Human Rights Watch, to provide the names of the businesses listed on it, or to reveal the businesses’ total declared value.[5 ]

They said the data supplied by the TNI could not be considered final because it was “very rough” and included many entities that, in their view, did not constitute “real businesses.”[6]

According to these officials, the list incorporated many small-scale ventures, some with assets of negligible value, alongside other, much larger enterprises.[7]

In the meantime, public statements offer some indications. In mid-2005, unnamed officials told the Singapore-based Straits Times newspaper that the top twenty or so military companies in Indonesia had a total estimated annual income of $200 million.[8]

For the sake of comparison, perhaps the best available historical figure is one used by foreign finance officials. An “informal review” of a selection of eighty-eight military businesses in Indonesia found that they had a combined turnover of Rp. 2.9 trillion ($348 million) in 1998/1999.[9] The Far Eastern Economic Review, referring to the same study, further revealed that annual revenue from the selected military businesses amounted to approximately Rp. 500 billion ($60 million).[10] Contrasting this to the $200 million figure offered in mid-2005 (which covered a smaller number of companies), it appears that those military businesses that survived the Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s were able to rebound significantly from that low point. (See below for additional data specifically for businesses held under military foundations.)

Illustrative Diagram of a Military Business

Click Here for large diagramNote: This example is provided here to demonstrate the ownership structure of military businesses and does not purport to make a substantive claim about the businesses listed. It is based on information provided by TNI headquarters and supplemented by two people familiar with the navy’s businesses because they reviewed them (in one case, as part of an internal review by the navy and in the other independently). (Information as of May 2006.)

Link:

Bila ABRI berbisnis: menyingkap data dan kasus penyimpangan dalam praktik bisnis kalangan militer

Bisnis militer Orde Baru: Keterlibatan ABRI dalam bidang ekonomi dan pengaruhnya dalam rezim otoriter

Australian Defence Business Review

The Indonesian Military After the New Order

Power Politics and the Indonesian Military

Table of Contents

Security services for freeport Indonesia

Some illegal business activities by Military

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH VOL. 18, NO. 5(C)

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------[1] In the Indonesian language, the defense ministry is called the Department of Defense but it is in English as

usually referred to as the Ministry of Defense.

[2] By comparison, according to a 2001 estimate provided by Minister of Defense Juwono Sudarsono, who

served a first term as defense minister from 1999 to 2000, the military then owned some 250 companies. ICG, “Indonesia: Next Steps in Military Reform,” ICG Asia Report, no. 24, October 11, 2001, p. 13. It is reasonable to assume that the 2001 figure reflected the outcome of an effort Sudarsono announced a year earlier, in which the defense ministry was “cooperating with the TNI headquarters to find out the number of foundations, cooperative units or companies owned by the TNI.” “Indonesian minister warns…,” AFP.

[3] Major General Suganda, “TNI commits to reform…,” Jakarta Post.

[4] Human Rights Watch interview with a person involved in that review, Jakarta, April 18, 2006.

[5] Human Rights Watch interview with Lt. Gen. Sjafrie Sjamsoeddin, secretary-general of the Ministry of Defense and former TNI spokesman, Jakarta, April 12, 2006; Human Rights Watch interview with Muhammad Said Didu (commonly known as Said Didu, the name used hereafter in this report), secretary of the Ministry of State-Owned Enterprises, Jakarta, April 19, 2006.

[6] The question of how the government would define military business for the purpose of implementing the TNI law’s mandate that these businesses be transferred to government control is discussed further below (see the chapter on “Obstacles to Reform”). Human Rights Watch interviews with Lt. Gen. Sjafrie Sjamsoeddin and Said Didu, April 2006.

[7] Ibid.

[8] John McBeth, “Tough job to wind up Armed Forces Inc,” Straits Times, June 4, 2005. The remaining formallyestablished military businesses were considered not to be economically viable. Ibid. Elsewhere, the total value of the military’s business holdings has been estimated, variously, at Rp. 326 billion (more than $35 million), Rp. 10 trillion ($1.06 billion), and more than $8 billion, to offer but a few examples. In most cases, it was unclear how these figures were calculated.

[9] The data was cited in a report prepared for international donors. World Bank, Accelerating Recovery in

Uncertain Times: Brief for the Consultative Group on Indonesia (Washington, DC: World Bank, 2000), p. 29.

[10] John McBeth, “The Army’s Dirty Business,” FEER, November 7, 2002. The article, presumably using 2002 exchange rates, gave the dollar equivalent as $55.5 million.

Book review:

| Military Reform and Democratisation |

| Indonesian Military Politics |

| The United States and the Indonesian Military |